The gunner knew his piece, and it seemed to him that she must recognize her master. He had lived a long while with her. How many times he had thrust his hand between her jaws! It was his tame monster. He began to address it as he might have done his dog.

The gunner knew his piece, and it seemed to him that she must recognize her master. He had lived a long while with her. How many times he had thrust his hand between her jaws! It was his tame monster. He began to address it as he might have done his dog.

“Come!” said he. Perhaps he loved it.

He seemed to wish that it would turn towards him.

But to come towards him would be to spring upon him. Then he would be lost. How to avoid its crush? There was the question. All stared in terrified silence.

Not a breast respired freely, except perchance that of the old man who alone stood in the deck with the two combatants, a stern second.

He might himself be crushed by the piece. He did not stir.

Beneath them the blind sea directed the battle.

At the instant when, accepting this awful hand-to-hand contest, the gunner approached to challenge the cannon, some chance fluctuation of the waves kept it for a moment immovable as if suddenly stupefied.

“Come on!” the man said to it. It seemed to listen. Suddenly it darted upon him. The gunner avoided the shock.

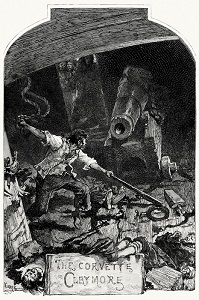

The struggle began – struggle unheard of – the fragile matching itself against the invulnerable; the thing of flesh attacking the brazen brute; on the one side blind force, on the other a soul.

The whole passed in a half-light. It was like the indistinct vision of a miracle.

A soul – strange thing; but you would have said that the cannon had one also – a soul filled with rage and hatred. This blindness appeared to have eyes. The monster had the air of watching the man. There was – one might have fancied so at least – cunning in this mass. It also chose its moment. It became some gigantic insect of metal, having, or seeming to have, the will of a demon. Sometimes this colossal grasshopper would strike the low ceiling of the gun-deck, then fall back on its four wheels like a tiger upon its four claws, and dart anew on the man. He, supple, agile, adroit, would glide away like a snake from the reach of these lightning-like movements. He avoided the encounters; but the blows which he escaped fell upon the vessel, and continued the havoc.

An end of broken chain remained attached to the carronade. This chain had twisted itself, one could not tell how, about the screw of the breech-button. One extremity of the chain was fastened to the carriage. The other, hanging loose, whirled wildly about the gun, and added to the danger of its blows.

The screw held it like a clenched hand, and the chain, multiplying the strokes of the battering-ram by its strokes of a thong, made a fearful whirlwind about the cannon – a whip of iron in a fist of brass. This chain complicated the battle.

Nevertheless this man fought. Sometimes, even, it was the man who attacked the cannon. He crept along the side, bar and rope in hand, and the cannon had the air of understanding, and fled as if it perceived a snare. The man pursued it, formidable, fearless.

Such a duel could not last long. The gun seemed suddenly to say to itself, “Come, we must make an end!” and it paused. One felt the approach of the crisis. The cannon, as if in suspense, appeared to have, or had – because it seemed to all a sentient being – a furious premeditation. It sprang unexpectedly upon the gunner. He jumped aside, let it pass, and cried out with a laugh, “Try again!” The gun, as if in a fury, broke a carronade to larboard; then, seized anew by the invisible sling which held it, was flung to starboard towards the man, who escaped.

Three carronades gave way under the blows of the gun; then, as if blind and no longer conscious of what it was doing, it turned its back on the man, rolled from the stern to the bow, bruising the stem and making a breach in the plankings of the prow. The gunner had taken refuge at the foot of the stairs, a few steps from the old man, who was watching.

The gunner held his handspike in rest. The cannon seemed to perceive him, and, without taking the trouble to turn itself, backed upon him with the quickness of an axe-stroke. The gunner, if driven back against the side, was lost. The crew uttered a simultaneous cry.

But the old passenger, until now immovable, made a spring more rapid than all those wild whirls. He seized a bale of the false assignats, and at the risk of being crushed, succeeded in flinging it between the wheels of the carronade. This manoeuvre, decisive and dangerous, could not have been executed with more adroitness and precision by a man trained to all the exercises set down in Durosel’s “Manual of Sea Gunnery.”

The bale had the effect of a plug. A pebble may stop a log, a tree branch turn an avalanche. The carronade stumbled. The gunner, in his turn, seizing this terrible chance, plunged his iron bar between the spokes of one of the hind wheels. The cannon was stopped. It staggered. The man, using the bar as a lever, rocked it to and fro. The heavy mass turned over with a clang like a falling bell, and the gunner, dripping with sweat, rushed forward headlong and passed the slipping noose of the tiller-rope about the bronze neck of the overthrown monster.

It was ended. The man had conquered. The ant had subdued the mastodon; the pygmy had taken the thunderbolt prisoner.

The marines and the sailors clapped their hands.

The whole crew hurried down with cables and chains, and in an instant the cannon was securely lashed.

The gunner saluted the passenger.

“Sir,” he said to him, “you have saved my life.”

The old man had resumed his impassible attitude, and did not reply.

Excerpt from “Ninety-Three” by Victor Hugo ~~Loose cannon~~

Filed under Fiction, Literature

Victor Hugo was born in Besançon, France on 26 February 1802, and died in Paris on 22 May 1885, aged 83 years. ‘Ninety-Three’ was published in 1874.